F.A.Q.

Certain questions about our courses seem to come up all the time and we have tried to answer these as fully as possible below. Click on each title to see the full explanation, and please don’t hesitate to contact us if you can’t find exactly what you are looking for.

EARLY BOOKING NOW ESSENTIAL FOR CLIMBING MONT BLANC

(Video version:)

Big changes to the Mont Blanc hut booking system have just been announced from 2022 onwards.

Rather than opening the reservation system in March/April as was previously the case, from December 2021 all pro Mont Blanc hut bookings for the following season will go online straight away and it will be strictly first come, first serve. The sooner you are able to commit to reserving your trip therefore, the better chance we will have to get hut places for you; unlike in previous years, if you leave your booking to late winter / early spring, the chances are there will be very little availability left.

Typical Gouter hut situation: Almost no places left

Ideally then you should aim to book 6+ months in advance, especially if you are fairly restricted as to when you can come. This would also give you a solid time frame for your training, and as for the last two years our COVID refund guarantee remains in place should travel restrictions suddenly be reintroduced.

Photo identity is going to be needed for each reservation from next season, and this should help prioritise genuine reservations over block bookings and give more availability and a fairer system overall, however potential ascensionists need to be aware that things have changed on Mont Blanc, and everyone who hopes to attempt the summit next season is probably going to have to be prepared to commit early.

John Taylor (Head Guide, MBG)

In 20 years of operation and 5000+ clients to date, the worst accident any has experienced was a broken ankle after tripping over crampons during a crampon training exercise.

In 20 years of operation and 5000+ clients to date, the worst accident any has experienced was a broken ankle after tripping over crampons during a crampon training exercise.

We are hugely proud of this record, but also very aware that it could all change tomorrow. So far we have had a total of one broken ankle (caught crampon during training exercise) and two broken wrists (fell over on a footpath and tripped over in a hut respectively); everything else has been cuts, sprains, and bruises, although there have been a couple of near misses as well. We occasionally have a precautionary helicopter evacuation for altitude sickness, but the victim has always recovered extremely fast, often before the helicopter reaches the valley. Our full accident history excluding (fully recovered from) altitude sickness, sprains, cuts, bruises etc. is shown below, and any future incidents will also be reported here:

Accident History (2004-2024)

2009: Guide suffered broken rib and considerable cuts and bruises after stopping client slip on steep snow descent gulley below Tete Rousse, and was lucky not to have been more seriously injured. All guides subsequently instructed to avoid this gulley in the future. No clients injured.

2011: Suspecting rock fall and therefore having left clients in the Tete Rousse hut for a “guides only” reconnaissance of the Grand Couloir, a guide was subsequently hit in the leg whilst still a long way from the couloir after a very large rock fall from below the Gouter hut. This rock fall was of an unprecedented size and even reached the camp site above the Tete Rousse hut. The guide sustained major bruising to his leg but fully recovered in a few days. No clients involved.

2013: Client tripped and fell breaking his wrist on the footpath just below the hut on Gran Paradiso whilst descending back to the valley.

2014: Client suffered broken ankle after tripping over crampons during crampon training exercise on the Mer de Glace glacier.

2018: Client suffered broken wrist after tripping over hut slippers at the Chabod hut.

2024: (Not an accident, but included for completeness) Client collapsed and subsequently died 100m above the car park on the first day of the course. Suspected heart attack, as yet unconfirmed.

Safety is absolutely paramount to us, and we consider our safety record as infinitely more important than our summiting record. We do not hesitate to turn back in marginal conditions or with overly tired clients, as even experts can come unstuck if they push the limits often enough. All our guides carry radios that allow them to talk to the rescue services or each other at any time and wherever they are on the mountain, this being particularly important due to the many areas still without mobile phone reception. Radios also make it much easier to change teams around if anyone is having a problem and needs to go down.

Accidents are always a possibility in the mountains, and the fact that an operator has had one does not in any way mean they are a bad operator as unfortunately it can happen to the best of us; to be clear most well known operators probably have safety records similar to ours. We are however very proud of our accident record to date and maintaining this standard will always be our top priority.

Unfortunately sometimes conditions on Mont Blanc are so bad it’s not even worth trying to go up there. If there’s any chance at all of making the summit, we’ll try for it (it’s what we’re all about after all), but if we’re just going to get soaking wet walking to the hut only to come down the next day we’re going to be better off elsewhere. (This could also be the case if a heatwave made the Grand Couloir too dangerous to cross for a time.)

At Mont Blanc Guides we’re determined to give you the best mountaineering experience possible whatever the conditions. Fortunately there is very often some other part of the alps where conditions are better and we will go wherever it takes to get better conditions, at no extra cost. A favorite is Monte Rosa (see below) which has the advantage of being a long way East of Mont Blanc and thus getting better weather in the common Westerly weather patterns. Strong teams can often get up all of the 4000m summits shown below, starting with Schwarzhorn (4321m) right up to Zumsteinspitze (4563m), this latter being only 250m lower than Mont Blanc itself.

If strong winds mean we need to go lower we might try some more technical mountaineering like the Traverse of the Entreves (below L) or the Cosmiques or Lawrence aretes on the Aiguille du Midi (below centre), and if even those are out we can often still get the Traverse of the Crochues (below R).

It’s really very rare that we can’t get on things like this even in fairly marginal conditions, and we’ll always do our best to find challenging objectives for you should Mont Blanc not be possible.

I am not a doctor, but I do have a lot of experience of how people (to date over four thousand) react to altitude on Mont Blanc. Mont Blanc Guides’ courses are all six days long, include four nights in high alpine huts and an acclimatisation / training peak of over four thousand metres. Isn’t this overkill just to climb to 4810m?

I am not a doctor, but I do have a lot of experience of how people (to date over four thousand) react to altitude on Mont Blanc. Mont Blanc Guides’ courses are all six days long, include four nights in high alpine huts and an acclimatisation / training peak of over four thousand metres. Isn’t this overkill just to climb to 4810m?

Well for some people yes it is, but for most of us no it really isn’t. Many years ago I encountered a large group of soldiers camping outside the Tete Rousse hut (3165m) who were planning on climbing Mont Blanc the following day; they had all come directly onto the mountain without acclimatising, and there were exactly 70 of them, all between 18 and 30 years old and all pretty fit looking. The following morning we counted 25-30 of them who had got no further than the Gouter hut (3800m) where we found them in a wretched state, and a colleague of mine subsequently spotted another 20 or so at the Vallot bivouac hut at 4300m, equally ill and unable to continue. Exactly 16 made it (I know this because I counted them as they came back past me), and of these 12 looked fine and 4 were green.

Scale this up and you get 23% of people who can go straight up Mont Blanc without acclimatising, assuming of course they’re fit enough already. How do you know if you’re one of the 23%? You don’t, unless you’ve already gone straight up to a similar altitude working hard and felt OK. Personally (and despite having climbed Mont Blanc more times than I can remember) I am well and truly in the other 77%, and rather towards the sick end at that.

How Does Acute Mountain Sickness Make You Feel?

Absolutely terrible, like the first time you got drunk at a teenage house party and ended up with your head down the lavatory with the coolness of the china pan as your only comfort (don’t ask me how I know this). Or really bad food poisoning accompanied by such a sudden and total loss of energy that standing up is difficult and walking up hill nearly impossible. Imagine feeling like that half way up a mountain and hours from rest, and you’re starting to get the picture.

What many people don’t realise is that AMS is rarely a gradual worsening of symptoms, such that it would be easy for a guide to turn someone around before things got too bad; rather, someone who minutes before was trucking along quite nicely suddenly transforms into a shambling vomiting wretch, barely coherent and almost incapable of further effort. This is why we are not willing to try our luck with someone who is “sure they will be fine” on a shorter program; AMS can rapidly turn a straightforward day into a fight for survival and there have been numerous fatalities on Mont Blanc when unacclimatized parties have become too ill to descend.

How Do Guides Deal With a Client With AMS?

If despite our preparation and screening efforts someone gets properly sick on Mont Blanc, very often our first recourse is to radio for a helicopter. In the vast majority of cases people get no worse than the stumbling / vomiting stage, but there is a very small percentage of people who can develop cerebral or pulmonary oedemas at alpine altitudes, so we prefer not to take any chances. The rate of recovery is astounding, usually the person is pretty much completely recovered as the helicopter touches down in the valley.

If despite our preparation and screening efforts someone gets properly sick on Mont Blanc, very often our first recourse is to radio for a helicopter. In the vast majority of cases people get no worse than the stumbling / vomiting stage, but there is a very small percentage of people who can develop cerebral or pulmonary oedemas at alpine altitudes, so we prefer not to take any chances. The rate of recovery is astounding, usually the person is pretty much completely recovered as the helicopter touches down in the valley.

Sometimes it’s not so easy, if the clouds come in helicopters can’t fly and teams have to get down to the hut (usually the Gouter) under their own steam. This is then usually followed by a fun 90 minutes in the “Gamow” pressure bag which though effective is not a particularly enjoyable experience, particularly for the guide who has to pump it up every two minutes.

So What’s the Bottom Line?

We do have a few cases of altitude sickness, but the vast majority of people have no problems acclimatising sufficiently during our 6 day program and the rare cases of someone being hyper sensitive to altitude usually occur on our training peak Gran Paradiso, where they are easier to deal with as the mountain is easier to descend. Less than 5% of our clients, who were otherwise fit enough, have to turn back due to altitude problems.

HOWEVER, whether you book with us, someone else, or even if you try Mont Blanc independently, I would urge you to take at least 6 days over it with at least 2 nights sleeping over 2500m beforehand and preferably climbing much higher than that in between. It’s time consuming and more expensive to do that, but start shaving days off and you could be setting yourself up for a pretty hideous experience. According to the rescue services, altitude sickness is by far the biggest single cause of helicopter interventions on Mont Blanc.

(John Taylor, Head Guide MBG)

Absolutely you can, as long as you realise it is a proper alpine climb, and in no way just a high altitude walk or hike. The vast majority of accidents on Mont Blanc are the result of a basic lack of mountaineering skill, and happen when people attempt it who are not properly experienced climbers. If you are going to join one of our guided courses you don’t need any mountaineering experience, but if you decide to go it alone it is absolutely essential, otherwise you will be putting your life at risk in a very real way.

Please see the video below for more information; it goes through the terrain involved and skills required to climb Mont Blanc unguided in detail:

“I KNOW I CAN DO IT”, “I NEVER GIVE UP” etc.

~ Boardroom Talk Doesn’t Work on Mountains.

The Wrong Approach

Though encouraging people is a big part of my job, I must admit “Apprentice -style” sound bites like the above make me feel a bit queasy. Determination on it’s own isn’t worth much if it doesn’t translate into action, and if you turn up to climb Mont Blanc armed only with assertions, a very demotivating experience will very soon be heading your way. The reason determined people summit mountains is because their motivation gets them out training beforehand, not because they grit their teeth harder than everyone else on the day. Indeed, excessive teeth gritting could even be the reason you don’t end up getting to the top.

When reality comes crashing in on groundless self belief it often leads to a rapid descent into disillusion and disappointment, in other words the exact opposite of what we are trying to achieve. Some people even end up having a mini psychological collapse on the mountain, becoming so uncommunicative and despondent that they can be quite hard to manage; there is such a gap between their perceived and actual abilites that as soon as things get hard a “does not compute” message arrives in the brain and everything seems to shut down. Willpower alone will no more get you up Mont Blanc than it will let you run a marathon in two and a half hours.

(Yeah right..)

Doing it Right

Everyone who decides to try Mont Blanc is highly motivated, the trick is applying that motivation at the right time. To give yourself the best chance of getting up Mont Blanc, turn your determination into hard work beforehand and get out there and get as lean and mean as you can; there’s really no substitute for this and the mountain is just waiting to give you a good kicking if you don’t do it. A positive attitude when you get here will certainly help, but if you use it to get out training more often in the run up to your trip, it will be much more effective. If you turn up properly prepared, you won’t need a positive attitude anyway will you?

Preparing to climb Mont Blanc is hard work and there are no shortcuts, but that’s what makes it so rewarding when you do finally get there. You’ll only make the summit if you put the work in beforehand and turn up properly prepared; it’s as simple as that.

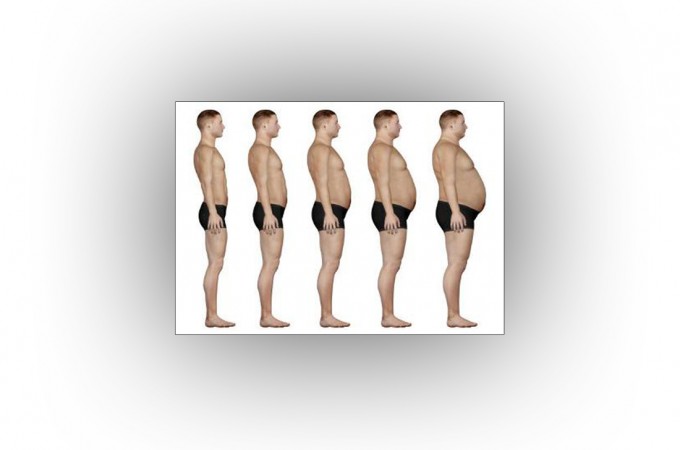

Since our first season in 2004 over 4000 people have signed up to climb with Mont Blanc Guides, and whilst I’m happy to say we’ve managed to get many of them to the summit of Mont Blanc, rather too many still turn up every year having underestimated the challenge. There is one overriding reason why people drop out of our courses, and it has absolutely nothing to do with lack of previous experience, climbing ability or determination. It can in fact be summed up in one word: overweight.

Climbing mountains is all about power to weight which is why we so ruthlessly go through clients’ rucsacs on the first morning and throw out all but the essential items. The ideal body type for this sort of activity is something you might see at a triathlon or marathon, it’s certainly not the sort of thing you would want for the beach. Very few of us (including me) are that skinny of course, but to have a good chance of getting up Mont Blanc you need to get into one of the first three categories above, otherwise the odds are going to be very much stacked against you.

To give an example, in 2014 one of our clients, Ian Kemp, made it up Gran Paradiso and battled to two thirds height on Mont Blanc before finally having to admit defeat when his legs gave out; Ian is a big strong lad but by his own admission he was just carrying too much extra weight to make the top. In 2015 Ian was back having lost 10kg, which is clearly a lot of weight to lose but as I say, Ian is something of a rugby player. This time he cruised to the top with no problems and told me afterwards he couldn’t believe how much easier it had felt. Ian very kindly wrote us a testimonial (go to 2015 then scroll down the the person in black with his arms out), but I think he gives us too much of the credit, as guides we can only take care of the safety and point people at the summit, after that it’s up to them. Ian’s achievement was entirely down to him and the result of his own determination to get in shape, and in my view never was a summit more thoroughly deserved (though he did tell me as he left how much he was looking forward to putting the 10kg on again!)

To summarise, you don’t need to be skinny to do this but if you are carrying a bit of “spare”, just try to get rid of as much of it as you can before coming to climb Mont Blanc, it really is the best thing you can do to improve your chances. Anything you can do will help, and while we won’t discriminate, you can rest assured the mountain will.

No it doesn’t, which is why you don’t need any previous mountaineering or climbing experience to join one of our courses. From the hut to the summit you hardly need to use your hands at all, occasionally for balance but not to pull yourself up. Having said that, climbing Mont Blanc could never be described as a walk or trek. Have a look at this video from one of our 2019 ascents, it shows clearly the type of ground involved:

Look at the photo showing the line of the route – to give an idea of scale, this would normally take 12 hours up and down.

The most technical section is the obvious dark rocky face in the foreground (which looks like the North face of the Eiger in this photo – it’s really not as bad as all that!). For the vast majority of this you would not need to use your hands but would scramble up (and down) as you would a steep flight of stairs. See the images below to give you an idea of what is involved. Note you are roped to your guide for the whole ascent. Above this section you climb some easy but tiring snow slopes before getting onto the top snow ridges, which though not difficult are certainly impressive and you need to be careful not to trip over your crampons, particularly in descent.

Our training climb of Gran Paradiso (4061m) in the first part of the week is designed to fully prepare you for all the types of terrain you will encounter on Mont Blanc. Hopefully by the time you get up there you will really be starting to know what you are doing!

Mont Blanc is a lump of ice and rock just like any other mountain. It’s true it does have a reputation as being an easy but unusually dangerous mountain, but it’s actually neither of these things. It’s a relatively straightforward climb if you are a fully experienced alpinist or with a qualified Mountain Guide – it’s the people trying it who are neither guided nor experienced that make up the vast majority of the accident statistics, and unfortunately there are a lot of people like this on Mont Blanc due to the mountain’s easy accessibility, which is in turn is what has caused it to be given this rather silly label.

Mont Blanc is a lump of ice and rock just like any other mountain. It’s true it does have a reputation as being an easy but unusually dangerous mountain, but it’s actually neither of these things. It’s a relatively straightforward climb if you are a fully experienced alpinist or with a qualified Mountain Guide – it’s the people trying it who are neither guided nor experienced that make up the vast majority of the accident statistics, and unfortunately there are a lot of people like this on Mont Blanc due to the mountain’s easy accessibility, which is in turn is what has caused it to be given this rather silly label.

The French believe strongly in the freedom of the mountains and there are no controls on the competency of potential ascensionists, anyone can try their luck and there are only a few signs warning of the potential hazards to the inexperienced. Perhaps it is this lack of restrictions that leads people to underestimate the danger, but then again how many light aircraft have warning signs that people with no flying experience should not attempt to take off in them?

The vast majority of accidents come from the most basic errors and would have been completely avoidable with even minimal training or experience, but the fact that the summit looks down invitingly on Chamonix tempts many complete novices to unwittingly take huge risks. People have often asked me mid ascent “Which one’s the summit?”, crampons hanging off trainers are a common sight, and a simple slip is often all it takes to cause a tragedy. As a colleague of mine once pointed out, when you see what people get up to up there it’s surprising there aren’t in fact more accidents.

It’s important to realise that most of these novices are not being willfully irresponsible but rather have no idea of the risks they are taking; if they knew they really were risking their lives, they wouldn’t go. They actually don’t endanger anyone but themselves as rescue services rightly will not set out in dangerous conditions, but unfortunately there are still dozens of serious and easily avoidable accidents on Mont Blanc every year.

Things have improved in recent years with more information available particularly on the internet, but it will always come down to a choice between more freedom/accidents and more regulation and control. Though the latter system would undoubtedly mean more work for professionals, most guides prefer the former more liberal approach– they were enthusiastic amateurs once, after all.

Accidents can happen to experienced parties as well of course and there will always be an element of risk in climbing mountains, but there is no comparison whatsoever between the safety margin of a professionally led party and that of a team of hopelessly under prepared amateurs. One might almost say it is like two different mountains.

(John Taylor, Head Guide MBG)

If you have never stayed in an alpine mountain hut before you may be pleasantly surprised by the level of comfort and service; there are a few useful things to know about staying in huts however, so please see the video below for a full explanation:

Crossing the Grand Couloir (translated meaning: large gully) makes up part of the technical scrambling section between the Tete Rousse and Gouter huts on the Gouter route it is shown by the nearly horizontal section at one third height on the red line on the photo below, the couloir being the broad parallel sided gully the route traverses. This area is a well-known accident black spot in dry conditions (i.e. when there is little or no snow on the face binding the loose surface rocks together) and stone fall can be channeled down the couloir to present a real danger to climbers crossing in between the relative safety of the sides.

There are quite simply times when rock fall makes the Gouter route unjustifiable. Each year is different: in 2013 and 2014 it did not happen at all, but between 2010 and 2012 there were perhaps two to three weeks a year affected on average, though not always at the same time of year. 2003 saw an unprecedented heat wave with the couloir impassable for half the season (fortunately Mont Blanc Guides started in 2004!), but to put that in perspective there were virtually no problems in the six years from 2004 to 2009.

Unfortunately 2015 turned out to be a mini rerun of 2003 with an intense heatwave hitting the alps in mid June. Summer temperatures in Chamonix (1000m) normally reach the high 20s and occasionally low 30s, but in 2015 there was a block of several days where the temperature passed 40°C, and the Grand Couloir was uncrossable for the best part of two months. This gave us our equal worst year since 2010 (when it didn’t stop snowing!) with a success rate of only 35%, hopefully this will not become any more regular than once every 12 years… 2016, whilst not as good as we would hope, was largely a return to normality with about a ten day period at the beginning of September where the couloir became too dry; 2017 we lost 10 days at the end of June then conditions stayed good throughout July, August, and September, and 2018 we lost two weeks at the start of August. Unfortunately we do seem to be having this happen for 10 days / two weeks quite often in recent years, the problem is however you never know when that period will be as it’s possible any time from mid June to mid September. (Update 2023: 2019 no problems, 2020 lost two weeks in August, 2021 no problems, 2022 major heatwave lost several weeks, 2023 lost 2+ weeks beginning of September).

Where an operator draws the line regarding “acceptable conditions” varies a bit, but it is Mont Blanc Guides’ usual policy to be the first to renounce the ascent if in any doubt and the last to resume it. Our safety record will always be much more important to us than our summiting record.

This is unfortunately all part of climbing Mont Blanc, though it can be hard to take especially if, as is often the case, the couloir becomes too dry during a spell of good weather. (Should this happen however we’ll head somewhere like Monte Rosa, only 250m lower than Mont Blanc). All it takes to bring Mont Blanc back into condition is a cool period with some new snow, so we really won’t know what will happen on your week until you get here. Unfortunately however many climbers try to force the issue and this leads to the often avoidable accidents that take place in the Grand Couloir every year. When the couloir is dangerously dry and the rocks are falling, the route is simply not there to be climbed.

Have a look at our video all about the type of boots you need for Mont Blanc: (there’s a text version below if you prefer)

Boots for Mont Blanc are very specific in that they must have rigid soles to give support for several hours of crampon work and be sufficiently insulated to deal with sub-zero temperatures. A typical example is shown below:

La Sportiva Nepal Evo Extreme, the choice of many of our guides. Great for Mont Blanc but too stiff for general trekking.

If you tried to bend this sole with your hands you would barely move it a millimetre, and though this is not ideal for general trekking it really comes into its own when wearing crampons. This is a “B3” boot on the B1-B2-B3 scale you sometimes hear talked about in climbing shops, and if you bring your own boots they will need to be B3 standard (B2 boots are more flexible and less well insulated and are designed for short term crampon usage at lower altitudes; you can sometimes get away with them on Mont Blanc if it’s particularly warm but B3 fit crampons better and are always warm enough).

If you have boots you’re not sure about either bring them with you anyway or send us a photo and we’ll let you know if they are good enough. Most of the people who develop blisters on our courses do so in boots they bought specially for the trip; if in doubt it’s definitely better to rent from us, we have taken a lot of trouble over our selection of hire boots and we’re happy to give you all the help you need getting the right pair on the first morning when we’re checking equipment.They can also be changed mid-week of course if you’re not happy with them and would like to try a different size or model.

A good trekking boot, but not stiff or warm enough for Mont Blanc

Specialising exclusively in climbing Mont Blanc allows us to constantly refine our course program to give the maximum flexibility and the best possible chance of being able to change the schedule and attempt the summit however, even on one of our programs experience has shown that there is still a 33% chance of being stopped by the weather.

This will always be the case with Europe’s highest mountain and is very much part of mountaineering in general, but we are confident we will be able will to find other exciting objectives for you (sometimes even harder than Mont Blanc to take your mind off the disappointment) so you’ll still have a great holiday. Note also that roughly a third of our testimonials are from clients who were unable to attempt Mont Blanc. This average 66% or two-third success rate also varies greatly from year to year.

| % MBG COURSES | |

| YEAR | SUMMITING |

| 2005 | 65% |

| 2006 | 80% |

| 2007 | 50% |

| 2008 | 65% |

| 2009 | 80% |

| 2010 | (wind/snow) 35% |

| 2011 | 60% |

| 2012 | 70% |

| 2013 | 70% |

| 2014 | 75% |

| 2015 | (heat wave) 35% |

| 2016 | 50% |

| 2017 | 60% |

| 2018 | 70% |

| 2019 | 80% |

| 2020 | COVID (45px only) 50% |

| 2021 | 80% |

| 2022 | (heat wave) 40% |

| 2023 | 60% |

| 2024 | 70% |

N.B. these statistics are all based on the number of courses able to reach the summit, they do not represent the total number of people who actually made it which would be lower (see fitness page). It is also worth noting that the reasons for the two worst years were different, 2010 was a year of incessant snow and wind whereas in 2015 an intense heatwave hit the alps and made the grand couloir too dry to cross safely for most of the middle part of the season.

Unfortunately it doesn’t take much in the way of bad weather to make Mont Blanc’s narrow summit ridges dangerous and it’s usually the wind that stops us, 40 km/h being about the safe maximum. Conditions deteriorate exponentially the higher you go, and on a given day a howling tempest on the summit (4808m) could be breezy snow showers at 3800m and even a calm sunny day in the valley. The flip side of this is we can still take on some other exciting objectives just by dropping down a bit.

Sometimes after our initial presentation on the first morning a client will take the head guide to one side and say something like the above. Obviously worried that the pace the guide will set on Mont Blanc will be too fast for them, they are in effect asking whether an exception might not be made in their case. They are sure they are fit enough to climb Mont Blanc, it’s just that theirs is not the kind of fitness that lets them move as quickly as everyone else.

There are two basic misconceptions here. The first is that the guide will set a pace which is faster than strictly necessary, thus leaving some margin for moving more slowly if specially requested. In reality there is no “standard” pace, each guide being trained to pick what his thinks is the best pace for his team, trying always to conserve their energy and maximise their chances of making the top. Constant communication is the key, and we will always let you go as slowly as we can as long as safety is not compromised. We want to get you to the top and will do so if it’s at all possible!

The second misconception is the idea that the slower you go, the higher you can eventually climb. In reality there is a point where the overall duration of the effort starts to tell and the cumulative effect of time at altitude leads to a rapid decline. This is a situation we must be careful to avoid.

Even on a bright sunny day there is a minimum (albeit as slow as we can make it) speed you need to be able to sustain. Your fitness levels make up a large part of our safety margin, and we need to know that you are operating slightly within your limits at all times; it’s actually a much slower pace than you would think, but if you really couldn’t hold the minimum speed you must accept that there was only one reason for it: you were simply not fit enough to go any faster.

For the majority of our courses the maximum group size is ten (occasionally 11). It is important to realise however that this is not a “group tour” and having more people in the group in no way affects the climbing experience as the guide: client ratio stays the same. It is actually advantageous on Mont Blanc as having several independent teams operating at once gives us more flexibility to change things around should someone need to go down.

For the majority of our courses the maximum group size is ten (occasionally 11). It is important to realise however that this is not a “group tour” and having more people in the group in no way affects the climbing experience as the guide: client ratio stays the same. It is actually advantageous on Mont Blanc as having several independent teams operating at once gives us more flexibility to change things around should someone need to go down.

The guide: client ratio on the Gran Paradiso training climb is 1: 3 or 1: 4 and on Mont Blanc is 1: 2, so for a course of ten we would have five independent teams operating on the mountain at the same time, all climbing at their own speed. As all teams are in radio contact with each other, descending faster parties who have already summitted can pick up anyone struggling and take them back to a hut.

The only real differences in being in a larger group are having more people around in the evenings, which is usually a positive thing as it helps build a team atmosphere. If you booked with someone else and would like to climb with them that is never a problem, though we may sometimes suggest putting teams of people of similar ability on the same rope as it generally makes for a smoother ascent.

The image below shows the “Cosmiques” or “3 Monts” route in red on the left and the Gouter route in green on the right (the Gonella route comes up from the other side and joins the Gouter at about half height). One starts the red 3 Monts route from the Aiguille du Midi cable car (3842m) and you might think therefore that this was the easiest way of getting to the top of Mont Blanc. Look more closely however and you will see how much steeper the ground on the red route is compared to the green Gouter route, and how much more climbing and descending is involved. Despite starting higher, the effort required to get up and down the red route is in fact significantly more than for the green route.

When it’s cloudy or windy rescue helicopters can’t fly and teams suddenly have to become very self-reliant. If someone gets altitude sickness mid way along the red route they could have major problems climbing back up to get out, and the objective dangers of seracs (unstable ice cliffs) and avalanche on the steep open slopes are also significant.

All in all then, despite its much higher starting point the 3 Monts route is a less reliable option than the Gouter or Gonella routes, as well as being more technically difficult. Though we have occasionally used it in the past, it is no longer part of out Mont Blanc program.